My little Harrison Milling Machine has a vertical head adaptor that takes power from the horizontal spindle, converting it into a conventional vertical milling machine. There was a version of this with step-up gearing but mine has the 1:1 version so my maximum speed is a rather lowly 1000rpm. (Though the VFD allows me to push this to 1400)

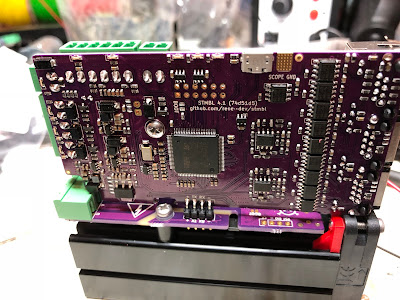

Unlike most of this model of milling machine mine is CNC and has a pneumatic power drawbar. But the vertical head is unmodified so the following should apply to all of them.

When I first got my mill I found that oil leaked out of the bottom bearing cover. I took it off and found no oil seal, so I added one assuming that Harrison were relying on the grease in the bottom bearing cover to keep the oil in the bevel box in.

Taking the head apart I realised that this was a misapprehension on my part, and that Harrison did actually know what they were doing. There is a sleeve fixed into the bottom of the casting which reaches up inside to above the oil level, and then a cup on the spindle shaft that comes down to below the top of this sleeve to stop oil falling in. The only way for oil to get in to the bottom bearing is if the oil level is set considerably too high. It seems likely that grease from the bearings will end up in the oil, though, after a few years of fills.

I had not been planning to take mine apart, despite the fact that it was very noisy. leading to concerns about the very expensive bearings. However after adding oil to the primary drive gear area it suddenly started to make a regular tapping/knocking noise so I decided to see what might be wrong.

The first thing to do is to remove the vertical head. It is a heavy and unwieldy device so it probably makes sense to start disassembling with it still mounted on the machine.

There are two oil spaces in the head, one for the step-up gears and one for the bevel box. There is a drain screw in the bottom of the rear casting for the former. The easiest way to drain the top is probably to remove the inspection cover on the right (5 Allen screws under the lubricant label) and then rotate the head through 90 degrees.

This would be a good time to loosen the screws on the bearing covers.

With the bevel drive drained it can be easily removed from the rear casting by removing the nuts from the 3 T-bolts and simply drawing it forward.

The T-bolts can be removed through the hole that is left when the top-hat bush around the zero-degree angle locking taper pin is removed. This is retained by a small grub screw.

The bevel bearing assembly itself can then be removed from the main body. It is retained by a number of socket screws.

There are two threaded jacking holes to help pull this assembly out. Two of the screws from the top bearing cover have the correct thread and can be used.

The bevel support housing will have been shimmed. Mine had two plastic shims, as shown below.

A

document that I found online says that bevel gears will have markings to say the correct offsets from the mating axis and backlash, but I could not find any such markings on these gears. I just had to assume that the existing shims were correct. I did not dismantle this assembly.

Note the three oil-drain holes in the main housing. These should be at the bottom when the housing is reinstalled.

Removing the spindle begins with removing the top nut and washer. It has three locking grub screws that bear on to the thread. Hopefully this hasn't damaged the thread too much (it hadn't on mine)

The spindle is a very tight fit in the top bearing inner race. In fact on mine it was too tight for the adjusting ring to move. There is no "nice" way to push it out without reacting the force against the top bearing. I ended up using an aluminium drift and a big hammer. A press would have been nicer.

To remove the spindle it is necessary to progressively unscrew and slide a number of parts off of the spindle. Starting at the top there is a collar above the bevel gear, then the gear, then a spacer and then the combined oil control cup and adjuster. The upper ring and cup adjuster also have three locking grub screws each.

I was stumped for a little while about the drive key for the bearing, and how to get it out to allow the spacer and adjuster to pass. Eventually I realised that both the spacer and the adjuster have a keyway slot, so they can slide past. The adjuster comes off of its threads before it hits the key.

This picture shows the oil-control sleeve which stops the oil falling out through the bottom spindle bearing:

With a bit of a fiddle and some carefully-applied brute force the spindle was removed.

The inner race was not removed. I don't know how you would, but it might well be possible to push it off using the 4 threaded holes in the 30-INT mounting face. These must be through-holes as the grease comes out through them.

The inner and outer bearing races and the cage are held together by snap-rings (by a nylon ring on the bottom and a wire ring on the top in my case)

The bearings are a bit fancy, with hand-engraved ID etc.

The internal baffles top and bottom would make bearing replacement a bit of a game. However there is space underneath the race for a hook-shaped puller of some sort. The baffles seem to be held in with small grub-screws radially onto their edge.

I took the rollers out to clean them. They all have a hole right through the middle (for cooling in oil-lubricated situations maybe?). The rollers are subtly tapered, it would probably be a bad idea to get one the wrong way round. In the picture below the one highest in the frame is small-end up, the rest are big-end up.

After a clean and re-grease of the bearings assembly was the reverse of disassembly.

A spanner on the drive dogs can be used for holding the spindle while the various rings are tightened.

I am using a punch here, but a modified C-spanner from an ER20 collet set was better for final tightening.

The document on bevel gears that I linked to above says that the gears should be set to the backlash engraved on the gears. Mine had no such number, so I had to guess. But I did measure it.

The primary drive gear assembly presents no special problems, except for one, and I forgot to take any photos.

The gear and 30INT adaptor arbor, along with the oil seal cup can be removed as a unit once the oil control baffle is removed. This is located only by a grub-screw on the operators-right of the machine.

It presses radially onto the baffle. With this loosened the baffle plate and the gears / shaft can be removed. There are tapped holes in the baffle plate, probably for a puller. But I found that I could remove mine using the gear/shaft as a slide-hammer to gradually work it out.

There is an O-ring around the baffle, but mine was completely flattened. I may source a new one at some point, especially if leaks turn out to be an issue.

I found that the drive-dog area on my spindle adaptor was fatigue cracked and had parts missing on both sides. I made a new input shaft out of a 30-INT to No 5 Jacobs Taper adaptor (The No5 Jacobs taper is _huge_).

For reference the bearings are listed in the parts book as:

355X / 345B bottom spindle bearing - Simply Bearings used to have these at £275 but not any more.

28137 / 28315B top spindle bearing (£243. They also have a Gamet bearing with the same OD and ID but it is deeper and that would be a problem)

28150 / 28315B (x2) bevel carrier bearings. (£121)

These bearings have flanges on the outer race and fit into plain bores in the castings.